Lordship and City Commune: Forging Bonds with the Country

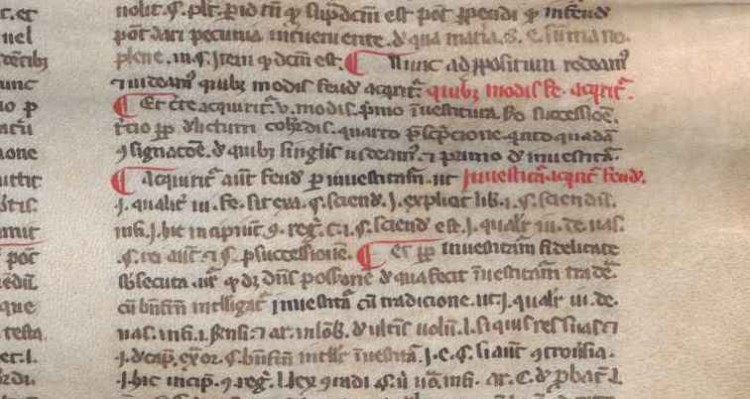

1166 June, Sabbion (Verona)

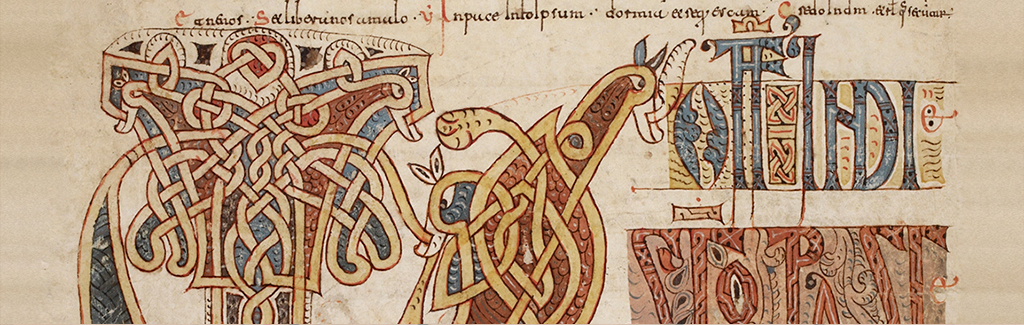

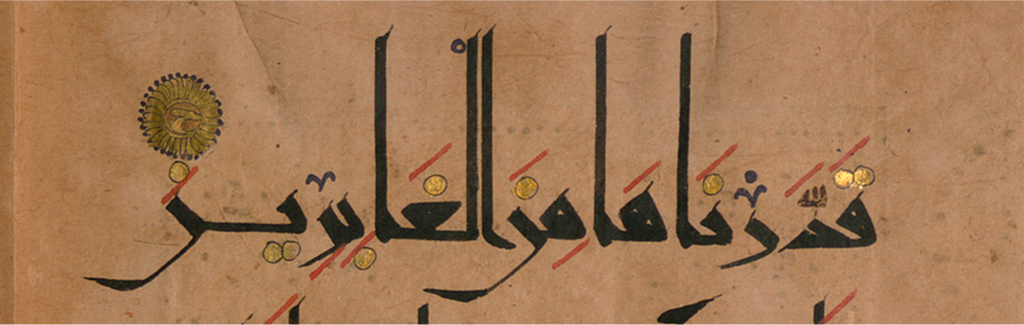

Archivum Secretum Vaticanum – Fondo Veneto I, perg. 6952

Azo was invested of his straight fief (feudum rectum), and swore his fealty “against all men, reserve his fealty to the lord Emperor”.

Iohannes de Bruno was invested and swore fealty.

Martinus de Vita was invested and swore fealty.

Ugozone was invested and swore fealty.

Morandus was invested and swore fealty.

Oto was invested and swore fealty.

Warientus was invested and swore fealty.

Grasso was invested and swore fealty.

Garzonus was invested and swore fealty.

Ubertus confessed he had sworn fealty.

Vivenzonus did the same.

Martinus de Garzone was invested and swore fealty.

Ubertus de Vita was invested and swore fealty.

Benzolinus was invested and swore fealty.

Tolbertus did the same.

Superbia was invested and swore fealty.

Vivianus was invested and swore fealty.

Ugo was invested and swore fealty.

Idraldus was invested and swore fealty.

Vivianus de Bosceto was invested and swore fealty.

Ubertus gave surety in the hands of the lord Vivianus, prior of the church of St Giorgio, under pain of 10£, about his ban and offence, that he will respect his command. Duchellus stands surety; Bossceto stands surety.

Bovazanus swore fealty to lord Vivianus, to the church of St Giorgio, and to his brothers, as a serf (famulus) against all men. His brother Astulfinus swore the same fealty.

Witnesses: judge Bonuszeno, Falconetus, Armannus and others.

In the year of the Lord 1166, 14th indiction.

Made in Sabbion, in the domus of St Giorgio, in the end of June.

† I, Conradus, notary of the Holy Palace, was present and wrote.

- The historical circumstances

This record, written in a harsh, basic language, is a good example of the relationship between a lord and his vassals. Its actors are the prior of the urban church of St Giorgio in Braida (Verona), and some villagers of Sabbion, a small settlement 40km east from the city.

It dates back to June 1166. At the time, Verona was one of the Italian communal city-states, formally subject to the German emperors, yet almost completely independent in practice; emperor Frederick I Barbarossa was attempting to restore his ancient rights in the Italian kingdom – deriving from the Carolingian conquest in the late 8th century.

In 1164, four communal cities of Veneto – Verona, Vicenza, Padua, and Treviso – after years of reciprocal conflicts, formed an alliance against the emperor, the Lega Veronese. On June 1166, while the notary Conradus was completing this record in Sabbion, Frederick I was in Germany, preparing a new military campaign in Italy. On November, he attempted to pass through Verona, all his army deployed after him. Nonetheless, for the first time in centuries an emperor could not cross the Alps through the “via di Germania” along the river Adige, for the Veronese army had blocked the path.

Some months later, the Lombard cities formed a wider alliance, the Lega Lombarda, claiming their autonomy from Frederick I. Pope Alexander III (1159-1181) incited the revolt: a decade of war between the emperor and the Italian communes was to come.

- Lordship and city commune: forging bonds with the country

In the twelfth century, the control of the district by the rising city-states passed through the control of (or alliance with) rural lords, in Verona’s case mostly urban families or churches. Residing the lords in the city, the forms of territorial control over the villages needed to rely on local classes of administrators, whose stability could have been determining in terms of continuity of seigniorial institutions, and thus of city-state political control.

St Giorgio’s prior went to Sabbion in person, for the first time after decades. Accompanied by the most important Veronese judge of the time, Bonuszeno de Lamberto, he received oaths of fealty from the local class of seigniorial administrators. Two men swore as serfs, and twenty vassals got confirmation of their fiefs, swearing in exchange their (military) fealty to the lord. Albeit the emperor was the common enemy, they nonetheless adopted a traditional formula: loyalty to a feudal lord shall not entail disloyalty to the emperor.

However, the city was preparing for war, and it was vital to keep the district united. Until this moment, the canons of St Giorgio had delegated local power to a rural lord who had linked to himself a class of local vassals. This record shows a key passage in the institutionalisation of the city district: From now on, written records from Sabbion would flow into St Giorgio’s archives; From now on, the élite of Sabbion, as well as many other villages, would deal directly with urban institutions, a great opportunity in terms of social mobility.

We know very well how a single event cannot change the course of history. But the contingent occurrence of different factors – the will of the city institutions to revive ancient traditions of political power over its district, peculiar relationships between city commune and rural lords, reciprocity of interests of local élites and seigniorial institutions, and, last but not least, the risk embodied by the upcoming conflict – accelerated a slow process of institutionalisation, making visible a city-to-countryside bond that would never be broken again for centuries.

Attilio Stella, University of Tel Aviv