Amantea in Calabria served as a Saracen stronghold from the late 830s to the late 880s. (Photo by Tommi P. Lankila)

Tommi Lankila. ESR7. Università degli Studi Roma Tor Vergata. Rome, Italy.

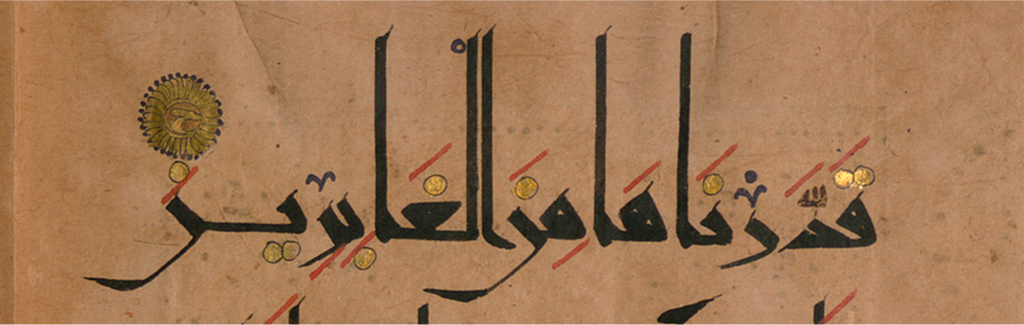

“God sent the avenging pagans,” we read in the life of Pope Sergius II (844-847) of the Papal Chronicle. The ‘avenging pagans’ were a new emerging force originally from the Middle East, under the aegis of Islam. They were known in Italy and the West as the ‘Saracens,’ the ‘Ishmaelites,’ or the ‘Hagarenes.’ I prefer using ‘Saracens’ or ‘Islamic forces’ instead of terms such as ‘Muslims’ and ‘Arabs;’ this was not a homogenous group, but rather consisted of Muslims, Christians, Arabs, and Berbers among others.

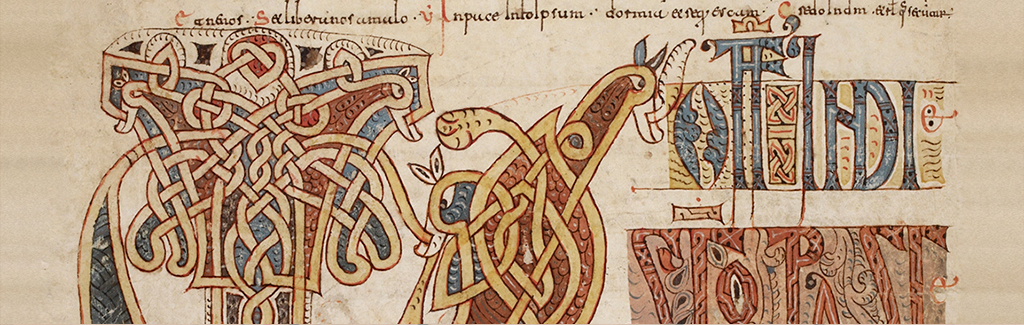

My interest lies in ghazawat, the study of the institution of maritime raids, which were conducted by ships and through maritime operations over the Mediterranean Sea. The geographical focus of my study is in the Central Mediterranean, mainly the Italian mainland and its nearby islands, Sicily, Sardinia, and Corsica. Here, I am studying the ‘impact’ that the Saracens had in this region, which left a clear mark in medieval writings. They talk about vast devastation of Christian lands, mass deportation of people into slavery, and of other kinds of people movements. The latter can mean either re-inhabition of ravaged areas by forced settlement (ordered by emperors and kings, or even by popes), immigration to new regions (Christian newcomers), or voluntary Muslim settlers from the Islamic lands, as is the case of the stronghold of Amantea.

Moreover, in my research, I want to analyze how the local Italian mainland and island communities were affected by the Saracen attacks. For instance, we see that the Saracen incursions had a vast impact in the minds of the Christian people, as many of these raids were directed against churches and monasteries. Therefore, I am interested in how the institution of saints can be used to study these incursions as we find traces of translations of holy relics in the face of the Saracen raids.

At the physical level, we know that several areas were badly devastated through fire, sword, and enslavement, and that if one was lucky enough to survive those perils, there remained the danger of famine and hunger resulting from burned fields or loss of stocks. Thus, my study will concentrate on what happened to the local small communities of peasants and how much they were affected by these attacks.

Another interesting point of study is that the upper class faced the Saracen menace and many noble men lost their lives during these wars, which opened avenues for social mobility; However, some Lombard and Byzantine members of the upper class decided to ally themselves with the Saracens in order to pave their own way to power and personal gain. In my research, I can therefore show that there were many high-ranking men, who actually benefitted from the Islamic presence in the region. Some of these men advanced their own status by threatening to attack using Saracen mercenaries, and others profited directly from cheap lands previously owned by those enslaved, killed, or forced to sell land in distress price. Ultimately, I am studying the Saracen raids as a valuable tool through which to understand the institution of social mobility in early medieval Italy.